A New Turkey

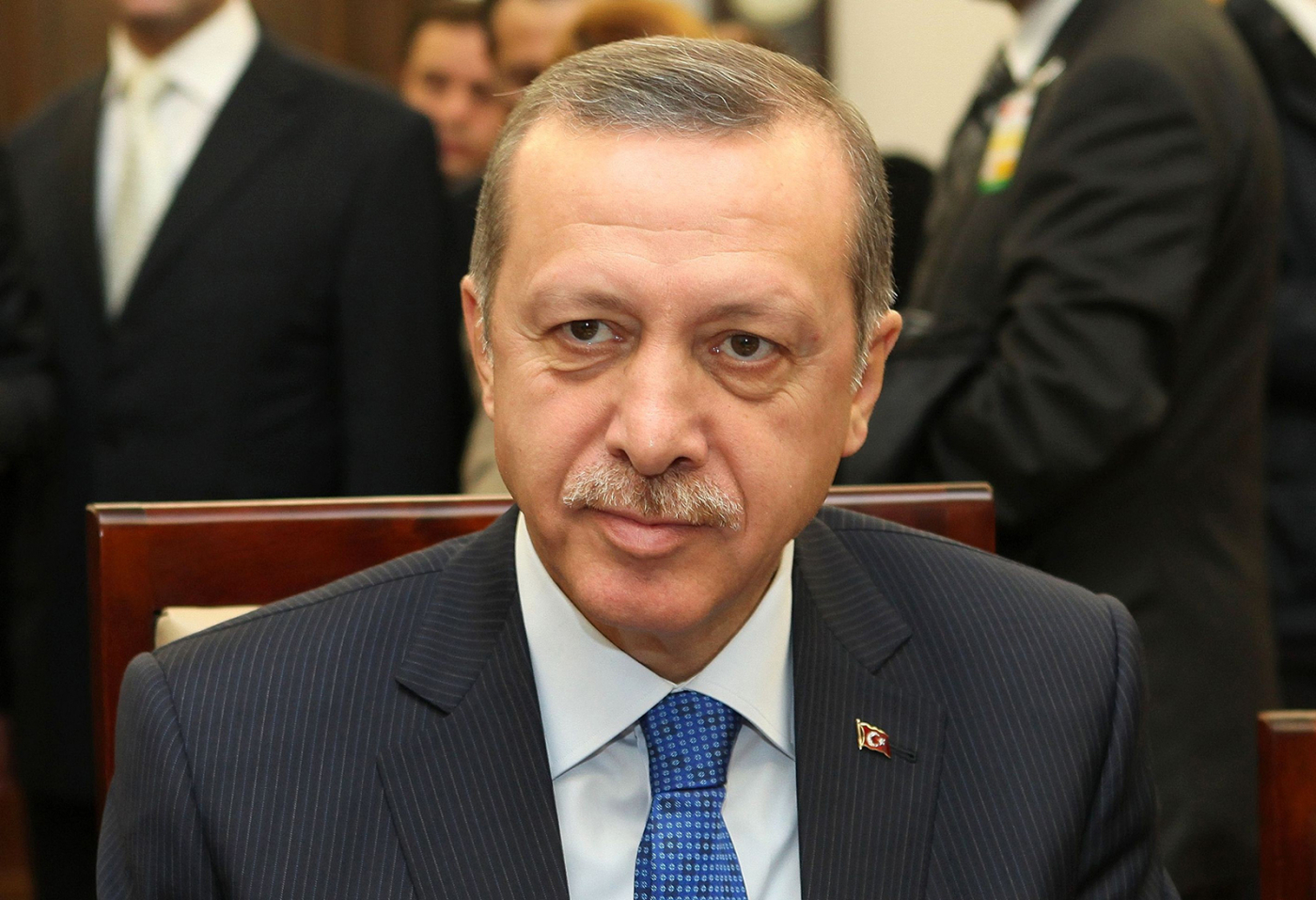

In 2017, Turkish people voted for a new constitution, giving the Turkish president Erdogan sweeping executive powers. According to Erdogan, the referendum was a victory for democracy: others now fear for a one-man rule. Either way, it raises questions about his intentions. His current hardline politics is a big contrast with the way he and his AK-party presented themselves when they came to power 16 years ago. In an interview with journalist Eelco Bosch van Rosenthal, legal scholar Prof Başak Çalı talked about the transformation of the Turkish democracy. What has changed? And what national and international effects does Erdogan's rule have?

Transformation of power

The AKP first won the elections in 2002. Back then, Turkey was in the middle of a big economic crisis, and Erdogan's party presented itself as the best suited candidate to lead Turkey out of it. The party took the majority of seats in the parliament, which meant they didn't have to form a coalition. For the first time in a very long time, a single party could make the decisions. As Turkey's prime-minister, Erdogan carried out a number of reforms that would not only lift Turkey out of its economic crisis, but would also enhance the rights of minority groups, and abolish the death penalty. Turkey, so it seemed, was on the road to democratisation and liberalisation.

This image changed around 2007, Çalı notes. Erdogan took strong measures to end the political influence of the Turkish army. He used a series of show trials to remove the top layer of the military: hundreds were sent to prison. This marked the beginning of a period of purging, which peaked in 2016 after the failed coup. Since then around 140,000 civil servants have been suspended, and tens of thousands have been arrested, with little prospect of a fair trial. So instead of following up on his promise of democratisation, Erdogan chose the path of 'authoritarianisation', with himself at the centre of Turkish power.

Turkey and Europe

In the early days of Erdogan's rule, Turkey drew closer to Europe: negotiations for full membership to the European Union began in 2005. But the process was slow and difficult, and would soon be stalled. As the political climate in Europe changed, some European leaders were increasingly hesitant to continue talks with Turkey. This led to frustration and distrust among the Turkish people. Did Europe really want Turkey as an EU-member? To add to the frustration, countries such as Bulgaria and Romania, which also didn't yet meet all requirements, were given EU-membership in a relatively short period of time. "The people in Turkey got tired of negotiating, tired of the cat and mouse game", Çalı says. Today, as the relation between Europe and Turkey has worsened, nobody takes the possibility of Turkey's accession to the EU seriously anymore.

Despite their troubled relationship, the EU and Turkey remain closely intertwined. Turkey is the EU's fourth largest export market and the fifth largest provider of imports. Moreover, the controversial EU refugee agreement with Turkey - an attempt to stop the influx of refugees to Europe - makes one even wonder who needs who more. Çalı: "At the moment, the EU might need Turkey more than the other way around."

While Turkey's relationship with the West deteriorated, Erdogan looked for other allies. Çalı: "Erdogan's attitude is clear: 'If Europe doesn't want us, we don't care'." In addition to strengthening its partnerships with China and Russia, Turkey has expanded its sphere of influence in the Middle-East and Africa, mostly for religious reasons. "Where interactions are most intense, religion seems to play a big role," Çalı states. It fits within the AKP's grander vision of Turkey as the leader of the modern Islamic world.

Masterplan

The transformation of Erdogan's rule raises the question: Was there always a grand plan? Çalı: "It's very hard to say. Next to being a reactionary leader, he is also very pragmatic and unpredictable." What is clear is that there probably will not be an end to Erdogan's power soon. "Given his control of the media and democratic institutions, it will get even easier for the AKP to win further elections", says Çalı. This means he will have time to mold the country according to his own design. What does this 'New Turkey' look like?