How security services respond to the fear of violence

'Please note: for your personal safety and the safety of others video surveillance cameras are constantly recording'. These words are a familiar sign of welcome as soon as you enter a shopping mall. You can also be sure to be greeted by a neatly dressed security guard and to hear the buzzing of metal detectors near the entrance.

Who installed these measures for safety? Not the government or national police. "The state is just one of many players in the field of security," says cultural anthropologist dr. Tessa Diphoorn (UU). Besides public services, private security companies (PSCs) are active as well. Very active. Since 9/11, the private security industry has grown immensely. Research by The Guardian from 2018 shows that worldwide, private security workers now outnumber public police officers. It's a $180bn industry, that is growing every year.

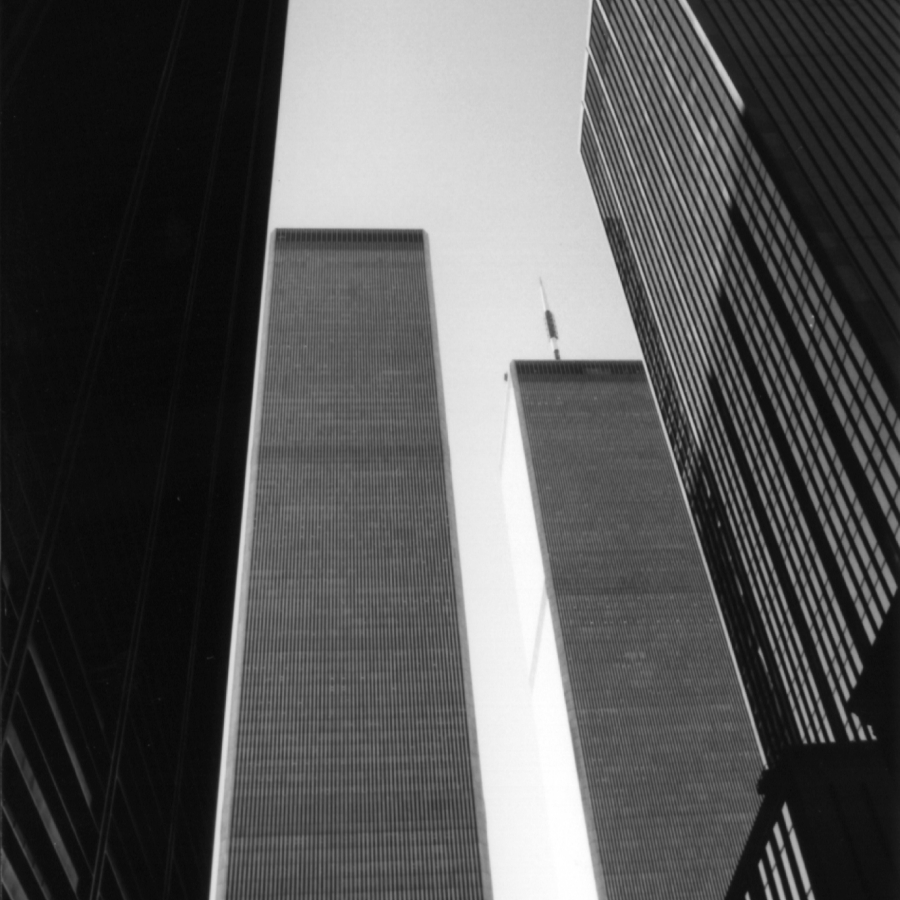

We have our own 9/11

"Private security services make money out of criminality," Diphoorn remarks. Their success depends on the number and extent of security measures customers take to stay safe. It's an interesting paradox: private security services are there to make us feel safe, but not too safe, since they profit from a sense of insecurity. They need to make us believe that we need more protection, no matter if the chances of crime are real or not. As long as people feel the threat, they'll buy the camera and hire the guard. The attacks on the Twin Towers helped fuel this sense of threat.

Although it's true that the 9/11 attacks gave PSCs a boost worldwide, it is important not to overlook the impact of local events, says Diphoorn. In September 2013, the Westgate Mall in Nairobi, Kenya was attacked by Islamic groups from Somalia. It was fear ignited by the Westgate attack that triggered the installment of extra security measures at the mall and the rest of Nairobi. Not left-over feelings of fear from the Twin Towers. In the words of Westgate's security director: "We have our own 9/11".

State security

How did the state strive to guarantee security after 9/11? According to legal expert Prof. Jan-Jaap Oerlemans (UU) there is a difference between the U.S. and Europe. In the U.S, everything was allowed for 9/11 to not happen again. The War on Terror got a solid legal basis in the Patriot Act, among others. Through these laws, Intelligence &: Security services got permission to collect personal data and information to detect and prevent the plotting of terrorist attacks.

Many people believe that the E.U. and its member states designed their own version of the Patriot Act. In the Netherlands, however, quite the opposite happened. In 2002, the Act on Security and Intelligence was installed. This act comprises a detailed list of which methods intelligence services may legally use to prevent terrorism and to what extent. Instead of extending surveillance power, this act works as a restriction on these powers.

Nor did the European Union mirror the U.S. response to 9/11. They were definitely measures to combat terrorism. Companies for tele-communication were licensed to collect and store customer data, for example, which intelligence services could use. But a European Patriot Act does not exist. Moreover, most anti-terrorism legislation in the EU is mostly motivated by what happened on this continent. Not so much what happened to the Twin Towers, but what happened to Madrid, Charlie Hebdo, Bataclan and Brussels Airport was reason for these new security measures, says Oerlemans. Just like Nairobi, Europe had its own 9/11.

Securing security

To do their work properly, security services must operate on the boundary of efficiency and integrity. It's a difficult act of balance, that is frequently undermined. Last month, Dutch newspaper NRC published a story about the Dutch National Coordinator of Terrorism and Security, which unlawfully collected personal data from thousands of people. In their hunger for data, it appears they went too far, Oerlemans comments.

While doing research in South Africa, Diphoorn saw how racial profiling is part of the private security industry's profit-making enterprise. PSC's can only make money if people think that they should be afraid of something or someone. And so private security companies actively spread the idea that black men form a threat. Discrimination and inequality, in other words, are part of their business model.

The question then is: who controls these security services, public and private? Both Diphoorn and Oerlemans conclude that oversight and checks on security service are there, but they need improvement. The private security branch already took steps to create a regulatory system, Diphoorn admits, but they're small. Companies can sign an international code of conduct and the so-called 'Montreux Document' containing 'legal obligations for good practice'. But these documents have barely been ratified. As for the public security services, steps for controlling their work have been bigger. But not big enough, Oerlemans explains. Legislation on the do's and don'ts of intelligence services are too vague and undetermined. A more universal system of control is needed.