Het afgelopen jaar gingen de ontwikkelingen in kunstmatige intelligentie razendsnel. Nieuwe AI-programma’s zoals ChatGPT, DALL-E en MidJourney, stellen ons in staat om in een handomdraai afbeeldingen en teksten te genereren. Een revolutie, volgens kenners. Maar er zijn ook zorgen. Volgens zakenbank Goldman Sachs zouden er 300 miljoen banen kunnen verdwijnen. Zijn die zorgen terecht? Een gesprek met arbeidssocioloog prof. Marleen Huysman (VU) en arbeidseconoom dr. Emilie Rademakers (UU).

Op sociale media stikt het van de aanbieders van gezondheidsbevorderende pillen, diëten, drankjes en therapieën waarvan de werking niet wetenschappelijke is bewezen. Wat is eigenlijk het verschil tussen wetenschap, pseudowetenschap en kwakzalverij? Moet de medische sector ook kritisch naar zichzelf kijken om te begrijpen waarom mensen voor het alternatieve pad kiezen? Luister naar een gesprek met wetenschapsfilosoof Stefan Gaillard (Radboud Universiteit en UMC Utrecht).

Spreker

Science Café Utrecht

Impact op de gezondheid

“Alle orgaansystemen in je lichaam kunnen worden aangetast door luchtverontreiniging”, vertelt dr. Ulrike Gehring, universitair hoofddocent bij de Universiteit Utrecht (Institute for Risk Assessment Sciences). Gehring onderzoekt de relatie tussen luchtkwaliteit en het ontstaan van ziekten bij kinderen. Door middel van een geboortecohort kon Gehring de gezondheid van 4000 jongeren jarenlang volgen en onderzoeken of de blootstelling aan luchtverontreiniging een effect heeft op de ontwikkeling van de longen. Naast kortademigheid, astma en COPD kan fijnstof ook een rol spelen in het ontstaan van hart en -vaatziekten, diverse soorten kanker en kan het zelfs het zenuwstelsel aantasten. Gehring: “Recent onderzoek laat effecten zien op zowel het ontwikkelende brein van kinderen, als snellere cognitieve achteruitgang bij ouderen.”

Toch is de slechte luchtkwaliteit in de stad geen reden om je hardlooprondje over te slaan. “De gezondheidsvoordelen van bewegen wegen op tegen de risico’s van het inademen van vervuilde lucht”, gaat Gehring verder. "Maar mensen kunnen wel gezondere keuzes maken. Kies bijvoorbeeld een groenere route uit, verder weg van het verkeer, en probeer niet tijdens het spitsuur te hardlopen, wanneer er veel verkeer is.”

Aan welke normen moeten we ons houden?

Het Longfonds, artsen en politici luiden de noodklok: De lucht in Nederland is ongezond en moet schoner. In Europa hebben we normen voor fijnstof en stikstofdioxide vastgelegd in het Europese recht en deze mogen niet overschreden worden. “Toch zijn deze normen onvoldoende om de gezondheid van burgers te beschermen”, zegt prof. dr. mr. Marlon Boeve, hoogleraar omgevingsrecht en gebiedsontwikkeling aan de TU Delft. De advieswaarden van de WHO zijn veel strenger. “Maar zowel op nationaal als Europees niveau zitten er nieuwe richtlijnen aan te komen, die toewerken naar de WHO richtlijnen.” benadrukt Boeve. In Nederland hebben we inmiddels het Schone Lucht Akkoord, waar gemeentes zich bij aan kunnen sluiten met als doel om de luchtkwaliteit van Nederland permanent te verbeteren. Het is alleen geen bindend akkoord en gemeenten zijn ook niet verplicht om het te ondertekenen. “Het Schone Lucht Akkoord is een stap in de goede richting”, begint Boeve, “Maar uiteindelijk heb je een harde grenswaarde nodig als je iets vanuit juridisch oogpunt wilt afdwingen.”

Burgerwetenschap voor schonere lucht

Luchtkwaliteit is een onderwerp wat iedereen aangaat en ook veel burgers verdiepen zich in dit onderwerp, merkte milieuepidemioloog Fleur Froeling MSc. Froeling betrok burgers in alle fases van haar onderzoek, zelfs bij het bedenken van haar onderzoeksvraag. “Ik vroeg aan mensen waar ze zich zorgen over maakte in hun leefomgeving”, vertelt Froeling. “Al gauw kwam ik toen op het thema houtrook.” Nog niet eerder werden burgers zó meegenomen in alle stappen van een milieu epidemiologisch onderzoek. Door het toepassen van burgerwetenschap verkreeg Froeling data die ze anders nooit had kunnen krijgen. “Burgers plaatsten sensoren en hielpen zo met het verzamelen van data over de luchtkwaliteit.” Uit het onderzoek van Froeling bleek dat er op dagen dat er veel houtrook in de lucht zat een toename was van kortademigheidsklachten en medicatiegebruik.

Hoewel de lucht in Nederland schoner is geworden, moet het nog beter. We moeten streven naar de WHO normen als we niet meer willen dat mensen ziek worden van de lucht. Bewustwording rondom luchtkwaliteit is belangrijk, niet alleen in de politiek maar ook onder de burgers. Op deze manier kunnen mensen gezondere keuzes maken als het gaat om fiets- of hardlooproutes. Maar voor écht schone lucht zullen we ons beleid moeten aanpassen. Dat moet wel lukken toch? Uiteindelijk ademen we allemaal dezelfde lucht in.

Wil je meer weten over de gezondheidseffecten van luchtkwaliteit, kijk dan hier het Science Café over Luchtvervuiling terug.

Zou je ook bij willen dragen aan onderzoek naar een gezonde leefomgeving? Meld je dan aan voor de panelstudie van de Universiteit Utrecht.

Wil je meer weten over hoe de Tweede Kamer debatteert over de Herziening Richtlijn Luchtkwaliteit? Kijk dan hier het debat van donderdag 6 april terug.

De afgelopen tijd is duidelijk geworden dat de zorg de patiëntenstroom bijna niet meer aankan. De oplossing ligt voor de hand: we moeten allemaal gezonder worden! Maar hoe doe je dat, als onze gezondheid voor een groot deel beïnvloed wordt door factoren waar we geen of weinig invloed op hebben, zoals luchtkwaliteit of sociaaleconomische achtergrond? Luister naar een gesprek met arts maatschappij & gezondheid dr. Marielle Jambroes (UMC Utrecht), ervaringsdeskundige armoede en sociale uitsluiting Eugenie Mac-nack (UMC Utrecht), en epidemioloog prof. dr. ir. Roel Vermeulen (UMC Utrecht).

Sprekers

Oorlog en vrede

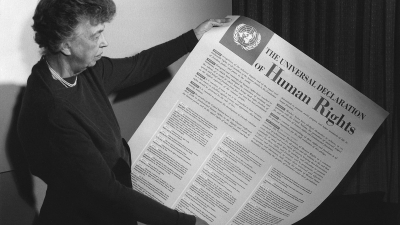

How are war crimes judged internationally?

“War is not Illegal.” Professor in International History Dr Iva Vukušić (UU) states. "There are regulations governing the conduct of war and permissible forms of attack." While it is legal to wage war, international treaties such as the Rome Statute aim to deter worse behavior. However, Vukušić contends that we cannot place all of our faith in these global frameworks. "The international justice system is only a tool for disaster management; it is not a blueprint for a just world."

Despite its formal name, the international judicial system is basically a conglomeration of independent organizations striving for relatively related objectives. The majority of these organizations, which deal with particular conflicts like the tribunals for Rwanda and Yugoslavia, were founded in the early 1990s following the end of the Cold War. With 123 participating state parties, the International Criminal Court (ICC) is at the center of these organizations. Individuals accused of international crimes such as war crimes, crimes against humanity, crimes of aggression, and genocide may be brought before this court.

“It is a small miracle that we have anything. If we had to start from scratch now, I'm not sure that any international criminal court would be established.” Vukušić says. She emphasizes, however, that there are shortcomings in the international judicial system. Vukušić explains, "Some very important states do not participate; the United States, China, and Russia are not members of the ICC." This is problematic since it only has jurisdiction over member nations or locations where a citizen of a member state has committed a crime. Another critique on the ICC is that it concentrates too much on African governments while ignoring sensitive crises in which powerful Western states are involved.

War crimes in Yemen

The crisis in Yemen serves as an example of how difficult it is to bring war criminals to justice. The UN has deemed Yemen, where 21.6 million people struggle to put food on the table, to be the worst humanitarian crisis of our time. The complicated geopolitical conflict between the Houthi rebels and the alliance commanded by Saudi Arabia is what led to this catastrophe. Throughout the ongoing battle both sides are charged with atrocities. However, using the ICC's assistance to obtain justice for the crimes committed is challenging. "The Rome Statute was never ratified by Yemen, Saudi Arabia, or the United Arab Emirates." Dr. Ewa Strzelecka (VU), a political anthropologist, begins to explain. "The ICC has very limited jurisdiction as a result." However, some efforts have been made to obtain justice. The European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights, for instance, is attempting to bring an International Criminal Court case against European arms corporations for their alleged involvement in war crimes. "However, these procedures take a very long time; a comprehensive 350-page file was filed in 2018, and we have yet to hear back." says Strzelecka. Vukušić asserts that not all crimes are admissible in the international judicial system for trial. "It is only a solution in a few cases; it is slow and imperfect."

Getting justice is hampered not only by the International Criminal Court's narrow jurisdiction but also by the dissolution of national courts. Strzelecka begins, "It's very difficult to persecute anybody on a national level." However, local judicial systems are also taking very significant steps to at least gather and document evidence. "This is also a prelude to a time when justice will truly be served."

Where do we go from here?

Vukušić encourages seeing the international justice system for what it is: “Flawed, politicized and with a lot of problems.” But the system is also something we can work with and improve. If it were up to Vukušić, she would know what to do. “One thing that would definitely help would be to reform the UN.” Five states hold veto power in the UN Security Council, resulting in an uneven balance of power. "It is not good that they can stop cases from going to the ICC." Furthermore, Vukušić would put more money toward stopping war crimes rather than waiting for something to go wrong. For instance, some months ahead of time, there were indications in the former Yugoslavia that things would go awry. Therefore, we should try to take away people's matches rather than fighting fires. Strzelecka also discusses her ideas for enhancing global justice. "Human rights, not the political interests of various nations, should be at the center of the institutions through systemic reform."

Watch the full recording with Vukušić & Strzelecka “How to get justice for war crimes?”

Further reading:

What is a war crime?

UN definition and rules on war crimes

Yemen

ECCHR: Made in Europe, bombed in Yemen

Lawyers seek ICC probe into alleged war crimes in Yemen

Gaza (Israel-Palestine conflict)

Chief prosecutor at the ICC Karim Khan on the inhumanity of the Israel-Palestine conflict

Ukraine

Ukraine: International Centre for the prosecution of Russia's crime of aggression against Ukraine

What does the ICC arrest warrant for Vladimir Putin mean in reality? | Vladimir Putin | The Guardian

Sudan

Genocide and war crimes charges against ex-President Omar al-Bashir

In je recht

Het juridische geslacht

“Het recht doet geen pijn, je voelt het niet als er op je geboorteakte een streep door je geslacht gaat.” Schetst jurist dr. Marjolein van den Brink van de Universiteit Utrecht. “Het is anders dan de discussie over een onomkeerbare medische ingreep.” Toch blijkt het aanpassen van een simpele “M” of “V” in het paspoort ook tegenwoordig nog niet zo simpel. Trans personen hebben nog steeds een deskundigenverklaring, van bijvoorbeeld een psycholoog, nodig voor het aanpassen van hun juridische geslacht. Waarom mogen we niet zelf bepalen welk geslacht er in ons paspoort staat?

Even terug naar het begin, wie begon er eigenlijk met het registreren van sekse in Nederland? Zoals veel van onze burgerlijke systemen, hebben we genderregistratie te danken (of wijten) aan Napoleon. “Napoleon wilde weten op hoeveel soldaten hij over een jaar of vijftien kon rekenen voor zijn veldtochten” vertelt Van den Brink. Deze registratie verliep niet geheel vlekkeloos, “Mensen dachten ‘ja, mijn kind krijg je niet!’ en zeiden en masse dat ze een dochtertje hadden gekregen.” Er ontstond een scheve geboortecurve en daarom werd het verplicht om de baby te laten zien. Tegenwoordig hoeft een baby niet meer fysiek meegenomen te worden voor de aangifte van de geboorte. In de geboorteakte wordt wel nog steeds het geslacht van de baby opgenomen.

Transgenderwetgeving

De meest recente transgenderwet komt uit 2014. Hierin is vastgelegd dat er geen medische voorwaarden vastzitten aan het veranderen van het geslacht van een geboorteakte. Trans man en -coach voor LHBTI+’ers Brand Berghouwer vertelt: “In Nederland was het tot 2014 zo dat bij het aanpassen van je geslacht in je paspoort, je jezelf moest laten steriliseren en je geen kinderen meer mocht krijgen” Schokkend om te beseffen en voor dit beleid heeft het kabinet excuses aangeboden. Ook is het door de wet van 2014 niet meer nodig om naar de rechter te gaan voor het aanpassen van het geslacht. Op dit moment kan een trans persoon met de verklaring van één deskundige een afspraak maken bij de afdeling burgerzaken van de gemeente, waar een ambtenaar van de burgerlijke stand wijzigingen in de geboorteakte en de Basisregistratie Personen (BRP) kan doorvoeren.

Trans activisten pleitten voor een nieuw wetsvoorstel voor de vereenvoudiging van de transwet uit 2014. Eén van de belangrijkste punten in de wetsaanpassing is dat trans personen vanaf zestien jaar geen deskundigeverklaring nodig hebben om hun geslacht in hun paspoort te veranderen. Dat is belangrijk volgens Berghouwer. “Het tast het zelfbeschikkingsrecht aan.” Zelf heeft hij zijn geslacht wel aangepast mét een deskundigeverklaring. “Maar ik heb dat wel gedaan met het bezwaar dat ik niet over mezelf mag beslissen.” Of de wetsaanpassing er gaat komen is onzeker, want na de val van het kabinet is de aanpassing controversieel verklaard.

Het tegengeluid

“Er is toenemende kritiek op het vereenvoudigen van de transgenderwet vanuit verschillende hoeken,” vertelt Van den Brink. Aan de ene kant heb je de mensen die tradities hoog willen houden. Dit is vooral een groep die streeft naar de conservatieve normen en waarden van een patriarchale samenleving. Trans personen en andere LHBTI+’ers passen niet in dit plaatje. Aan de andere kant heb je de genderkritische feministen. “Deze groep is bang dat de verworvenheden van de tweede feministische golf verloren gaan,” legt Van den Brink uit. Deze groep beargumenteert dat transrechten een gevaar zijn voor vrouwenrechten, omdat het bijvoorbeeld sportwedstrijden oneerlijk zou maken en de veiligheid van vrouwen in de gevangenis en blijf-van-mijn-lijfhuizen in gevaar zou brengen. “De zorgen van deze mensen zijn over het algemeen oprecht, al denk ik niet dat hun zorgen térecht zijn.” Uit onderzoek blijkt dat de anekdotische bewijzen die deze vrouwenorganisaties herhaaldelijk aanhalen slechts in een paar gevallen juist zijn, legt Van den Brink uit.

Inclusie- en exclusiesocioloog prof. dr. Niels Spierings van de Radboud Universiteit maakt zich zorgen. “Het tegengeluid klinkt luid. Dat wordt mede mogelijk gemaakt door de logica achter nieuws en media. Conflict- en negatief nieuws levert clicks en aandacht op.” Daarnaast gebruiken journalisten tegenwoordig sociale media als bron. Spierings: “Dan wordt er gezegd dat er veel kritiek is op sociale media, maar dat is niet representatief voor de samenleving. De grote meerderheid van Nederland denkt er vaak anders over.”

Hoewel de discussies rondom transrechten leidt tot verhitte discussies op platforms zoals Twitter, blijft het een feit dat transrechten ook mensenrechten zijn. Trans personen ervaren ongemak wanneer het geslacht op hun documenten niet overeenkomt met hun uiterlijk, met situaties met agressie en geweld tot gevolg. Dat ze hun geslacht niet kunnen aanpassen zonder deskundigeverklaring, tast het zelfbeschikkingsrecht aan. Voor de menselijke waardigheid van transmensen is het de hoop dat het wetsvoorstel vereenvoudiging van de transwet opnieuw kan worden ingediend.

Meer weten over transgenderrechten?

Bekijk dan de opname van de avond “Transgenderrechten onder druk”.

Of lees de volgende artikelen:

- Zeven vragen en antwoorden over de voorgestelde wijziging in de Transgenderwet

- Lees hier meer over de consultatie voor de Wet vereenvoudiging non-binaire geslachtsvermelding

Oorlog en vrede

‘Wederopbouw gaat niet zoals in de bekende kinderserie Bob de Bouwer: het is geen kwestie van wat cementzakken bij elkaar zoeken en aan de slag gaan’ vertelt sociaal wetenschapper prof. Thea Hilhorst (EUR). Burgers moeten inspraak hebben in de plannen voor wederopbouw, en het is belangrijk op een duurzame manier te bouwen die ook rekening houdt met de energietransitie waar we voor staan. Het liefst herbouw je op een manier die het gebied verbetert ten opzichte van de staat waarin het vóór het conflict verkeerde. ‘building back better’ is dan het motto.

Dat klinkt allemaal mooi, maar het herstellen van oorlogsschade heeft flink wat voeten in aarde. Waar humanitaire hulp zo snel mogelijk moet worden opgestart, is het belangrijk om bij het herstellen van oorlogsschade niet te overhaasten. Dat kan namelijk uitmonden in een oneerlijk resultaat, bijvoorbeeld waarin oorspronkelijke bewoners niet terug kunnen keren naar hun huizen, omdat de nieuwe woningen niet geschikt of te duur zijn geworden.

Snel starten met bouwen lukt vaak niet, bijvoorbeeld door onduidelijkheid over het eigendomsrecht van grond. Hilhorst: ‘In Oekraïne is het Kadaster echt niet op orde’. De rechtmatige eigenaar van een stuk land kan na het afronden van een bouwproject ineens op de stoep staan en eigendomsrechten claimen. Dat kan herstelprocessen met jaren vertragen.

Indien het lukt om een kapotgeschoten wijk weer te herbouwen, blijft er altijd een risico: het geweld in conflictgebieden laait vaak binnen vijf jaar weer opnieuw op. Het is natuurlijk erg jammer als nieuw gebouwde infrastructuur meteen weer vernietigd wordt door oorlogsgeweld. Een belangrijk deel van wederopbouw is dan ook het voorkomen van nieuwe conflicten, aldus Hilhorst. ‘Vorig jaar april stonden we al te debatteren over de wederopbouw in Oekraïne, maar het was nog helemaal niet duidelijk hoe de oorlog verder zou verlopen.’

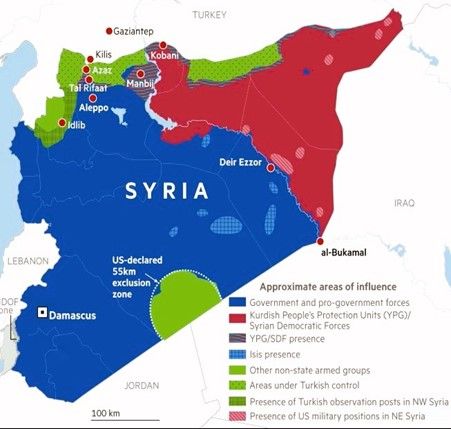

De politiek van wederopbouw in Syrië

Hoe ingewikkeld het opbouwen van een land kan zijn zie je in Syrië. Daar is geen centraal bestuur meer, maar het land is opgedeeld en staat onder controle van allerlei verschillende partijen: het regime van dictator Assad, de -deels Koerdische- Syrische Democratische Strijdkrachten, een leger dat door Turkije gesteund wordt en een jihadistische beweging (HTS) die is voorgekomen uit het Syrische Al-Qaidafiliaal. Conflictwetenschapper en voormalig ontwikkelingswerker Mohammad Kanfash (UU) legt uit hoe deze verdeeldheid het opbouwen Syrië bemoeilijkt.

‘We moeten in Syrië niet alleen denken aan herstel van schade, maar ook aan het opnieuw opbouwen van de staat zelf. Door de machtsdynamiek waar verschillende partijen aan mee doen, ontstaat er een nieuw strijdveld dat draait om de wederopbouw van Syrië.’ Bijvoorbeeld door de sancties die de VS oplegden aan het deel van Syrië dat door het regime van Assad wordt gecontroleerd. Deze sancties beperken en verbieden de wederopbouw. Niet alleen zorgen die er voor dat andere investeerders, zoals de Chinese en Russische, worden weggejaagd, maar ook dat het voor allerlei bedrijven heel moeilijk is om zaken als bouwmaterialen en zelfs voedsel te leveren aan Syrië.

De sancties zijn niet alleen streng, maar ook erg onduidelijk. Het is zelfs voor de advocatenteams van grote bedrijven heel moeilijk te voorspellen of een bepaalde overeenkomst met een Syrisch bedrijf toegestaan is. Dat zorgt ervoor dat Syrië in armoede vervalt: 90% van de Syriërs leeft in armoede, circa 46% van de volwassenen slaat maaltijden over zodat hun kinderen kunnen eten. Volgens Kanfash zijn deze sancties erg schadelijk voor de burgerbevolking en moeten ze dringend opgeheven worden

Kanfash trekt de beweegredenen van Westerse landen om de sancties te steunen, in twijfel. ‘Ze zeggen dat het is om “op te komen voor mensenrechten” en om te zorgen dat er geen precedent geschept wordt voor andere dictators in de regio’. Het doel is dus om Assad’s regime en oorlogsmisdaden niet te ‘belonen’ met geld en hulp, en om andere dictators uit de omgeving niet het idee te geven dat ze ongestraft hun eigen bevolking aan kunnen vallen en onderdrukken.

Misschien willen Westerse landen de sancties niet opheffen om een meer cynische reden, suggereert Kanfash: ze creëren bewust spanningen in een land door de bevolking in honger en armoede te laten leven, en daarmee de bevolking te stimuleren het regime omver te werpen. Het doel van het Westen zou zijn om Assad in toom te houden, en een vinger in de pap te krijgen in deze strategisch belangrijke regio.

Hilhorst en Kanfash zijn het eens dat in wederopbouw altijd de behoeften van burgers boven grotere politieke belangen moet staan, net als bij humanitaire hulp. Angst van hulporganisaties dat zij indirect een oorlogsmisdadiger steunen of dat het ingezamelde geld in de zakken van corrupte projectontwikkelaars verdwijnt is ‘gegrond, maar geen reden om dan maar niets te doen. Zaken als corruptie houd je altijd, maar mensen hebben recht op woningen en andere voorzieningen’ volgens Hilhorst. ‘En vergeet ook niet dat een land zichzelf wederopbouwt: mensen gaan echt niet wachten met hun huis repareren tot de oorlog voorbij is. Nee, die zoeken zelf wat bouwmaterialen bij elkaar en gaan aan de slag.’

In je recht

An increase in climate cases

The Urgenda case against the Dutch government and the milieudefensie case against Shell; climate activists are increasingly filing climate cases. According to the UN Environment Programme there have been 2,365 lawsuits relating to climate change around the world and almost 200 of those cases were filed in the past year. Climate lawyer Dr Tim Bleeker joined us at the evening “The road to climate justice” to talk about this increase in climate cases. According to Bleeker unease and shock could be felt in every boardroom across the Zuidas, the business district in Amsterdam. “Maybe it's not a charity thing to do something about climate, but maybe there are actual legal obligations now.” At first it was thought that companies didn’t have to abide by human rights legally since these rights address states and not companies, but this idea is changing. “Even though companies don't have to protect human rights they have to respect them.” Bleeker states. Mitigation and adaptation to climate change is a highly political issue, and states can be held morally accountable through law to take action. “Citizens or NGO’s can go to court if they feel that their rights are not being respected.”

Climate justice through just transitions

“Climate change is about a breakdown in the fundamentals,” according to political scientist prof. Fatima Denton. “It's a threat to energy security, water security and climate as a resource.” In her work Denton focusses on amplifying the voices of those on the frontlines of climate-related consequences. The countries in the Global South are often the most vulnerable to climate change, and contribute the least to the carbon emissions that cause climate change. In addition, the countries in the Global South have the least money and resources for climate adaptation. A just climate transition would therefore entail closing the climate adaptation finance gap. According to the UN Environment Programme the adaptation finance gap is now estimated at US$194-366 billion per year.

How do you take action to make countries less vulnerable to climate change? According to Denton the language used for climate action is not neutral. Net zero would be a good goal for a fossil fuel based western economy, but not for a developing country. “Decarbonization is not a problem in a country like Burkina Faso, because they don't have enough energy um to utilize,” Denton explains. Countries in the Global South deal with problems in food or energy security more often than western countries. These problems change the sort of action that needs to be taken. It is therefore important that people are able to explain and define what climate justice means to them. “If climate justice is defined for them, then it means that they have very little room to be able to say how it might affect them,” Denton says.

With the COP28 starting today, Denton is curious to study the power dynamics that will occur: who holds it and how is it used to control the trajectory where we are headed? “The type of transformation that we need to get ourselves out of this situation is a radical transformation,” Denton states. “This radical configuration from a carbon based economy to something less destructive and more resilient takes courage.” Where Denton hopes to inspire courage in leaders, Bleeker hopes to inspire lawmakers to make better laws for the climate. This is necessary, because until now, climate cases have not lead to binding legal consequences. For a real just transition, we need lawmakers to take action.

Do you want to know more about climate justice and how we can achieve just transitions? Watch the video of the evening "The road to climate justice" here.

Oorlog en vrede

Truth in the archives

For her book about communist Albania, prize-winning novelist Prof Lea Ypi (London School of Economics) dove into the Secret Service archives to find out the truth about the life of her grandma in post-war Communist Albania. After WOII, Albania was ruled by a communist party. This regime is considered to be one of the most brutal and isolated regimes in history. Characterized by inhumane prison conditions and forced labor camps, it resulted in the deaths of 25,000 people by execution, murder, starvation. Supporters of the former communist regime continue to deny the crimes and suffering caused by the regime. For many victims, the truth seems like the only way to move forward and deal with the past. “There is this hypothesis that only if you have truth, you will have reconciliation,” according to Ypi. With the book, she tries to challenge this hypothesis.

It turned out that the truth was hard to find in the files of the Secret Service, because they were a mess. The files contained a lot of scribbling: numbers, characters and smileys covered the pages. Ypi: “You can really see there was a bureaucrat there who was really bored doing the reporting.” These bureaucrats often made errors, stating for example that her grandmother was a widow when she was not. “Besides that, these archives don't really have any objective data, it’s always interpreted for you through a lens of propaganda and politics.” This struggle to find the truth inspired her to write the book as a novel, where a first person narrator takes the reader along in unmet expectations about the files. By retracing the steps of her grandmother and writing about her through fiction, Ypi was able tell the story in a more complete way than the archives did. “Truth lies not so much in the facts, but in the humanity of the reconstruction.”

Using art to tell the story

“You will never come to terms with the past by just thinking about the individual characters and how these individual characters collaborated or didn’t collaborate with each other.” Ypi states. You need to understand the broader context through newspapers and history accounts. To get this broader perspective you already need to be reconciled in your mind and be open to the perspectives which are completely different from yours. “Literature enables you to inhabit all these different characters.” Ypi expresses that looking at the world from a completely different perspective can be difficult. “You cannot condemn characters, even the flawed ones.” Art allows for a plurality of voices and perspectives and shows that it is not a particular individual that is to blame after a conflict, but rather a system of ideas. Take for example the neighbors of the Ypi’s that were high-ranking members of the party, but protected the Ypi family. “This is why it's very complicated. Some people, even within this oppressive system, tried to do the right thing and did have a moral compass somehow.” These kinds of stories make it difficult to say who was good and who was bad. It is important to realize there is no complete closure and there is no full truth. The post-communist truth is still highly politicized, Ypi believes there is always someone trying to deceive you or trying to exercise power in the files. Therefore, Ypi needed different tools in her philosophical search for truth. “Art rather than politics can bring reconciliation.”

Dignity and freedom amidst oppression

Through telling the story of her grandmother, Ypi gained many insights on what restoring dignity and humanity means. Despite being deported, being looked down upon, struggling for food and alone because her husband was a political prisoner, Ypi’s grandmother said she never felt unfree. “She had this idea that you know you are free, when you reject the pressure from society to conform.” Ypi says that her grandmother never accepted to be a spy, she wanted to live a moral life. Her whole life is a kind of example of someone going from one tragedy to another, but she considered herself free because she retained her humanity and never let the system dehumanize her. “I thought that was really important,” Ypi says “In a world in which we talk a lot about victimhood, but not about the agency of victims.”

In the process of reconciliation in Albania, hopes are high the archives will bring closure. But it is difficult to declassify the documents and make them accessible. In addition, the truth described in the archives is written in the language of the state. Altogether, people feel like there is no real way of finding out the truth about their family and feel robbed of their dignity. In her philosophical quest for truth, Ypi found the truth in fiction and art. However, Ypi is aware that art is also the result of ideology, propaganda, funding decisions and corporations. “But there is something in art that is not reducible to ideology.” Ypi argues that by striving for universality through art and inhabiting the different perspectives of characters you create something that can’t be reduced to solely ideology. “You get a better grasp of the history by having the multi-perspective vial view that art affords.”

Do you want to know more about what Ypi found in the secret service archives? You can watch the recording of the evening Historical Injustice and Reconciliation here.

Do you want to read more about Lea Ypi and communist Albania? Check out the links below:

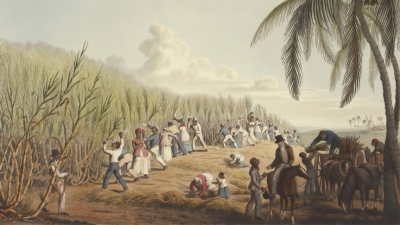

Ons slavernijverleden

De superioriteit van wetenschappers

"Op de universiteiten zijn veel wetenschappers die schrijven over het koloniale systeem, maar er is relatief weinig onderzoek gedaan naar de rol van wetenschappers in het koloniale systeem zelf. Ik wilde laten zien dat ook wetenschappers deel uitmaakten van het systeem.” Vertelde historicus en antropoloog dr. Henk van Rinsum aan RTV Utrecht. Van Rinsum dook in de koloniale geschiedenis van de Universiteit Utrecht en bundelde zijn bevindingen in een boek. Zelf is van Rinsum werkzaam geweest in de universitaire ontwikkelingssamenwerking aan de Universiteit Utrecht. "Ik ben ook op missie geweest. We wilden een idee overdragen, beschaving brengen."

Eigenlijk is dit idee van ontwikkeling al problematisch volgens Van Rinsum. Wetenschappers hebben in dat koloniale systeem gewerkt vanuit een zekere superioriteit tegenover de mensen die ze in de Global South (Zuid-Amerika, Azië en Afrika) tegenkwamen. “Die zagen ze als niet-ontwikkeld, primitief bijna.”

De overblijfselen van het slavernijverleden

“We hebben als Universiteit Utrecht tot nu toe enorm in een blinde vlek zitten staren”, vertelt historicus dr. Remco Raben bij de avond Wat we niet weten over ons slavernijverleden. “Kijk alleen al naar de campus in de binnenstad: de Universiteitsbibliotheek en de collegezalen zijn allemaal gevestigd in huizen van voormalige plantage-eigenaren. Bovendien waren er individuele hoogleraren aan de universiteit met aandelen in de koloniën, of ze waren zelfs plantage-eigenaar.” Ook profiteerde de Universiteit van het Nederlandse bezit van koloniën. “Met toegang tot de flora en fauna uit die gebieden zijn bijvoorbeeld de Utrechtse Botanische Tuinen opgericht en medicijnen ontwikkeld.”

Hoe nu verder?

Hoe moet de Universiteit Utrecht omgaan met haar koloniale verleden? En hoe willen we dat de UU in de toekomst samenwerkt met de universiteiten in de Global South?

Raben: “Een veelgehoorde tegenwerping over het veroordelen van het slavernijverleden is dat we het ‘moeten beoordelen naar de normen van die tijd’. Maar wiens normen zijn dat? Dat zijn de normen van slavenhandelaren en plantage-eigenaren. Pas als je kijkt naar de ervaringen en handelingen van de tot slaaf gemaakten, dan weet je wat de normen van die tijd zijn: zij maakten een einde aan hun leven, zij vluchtten of ze vergiftigden zelfs hun eigenaar. Dat betekent dus dat slavernij geen normaal leven was.” Dit koloniale verleden van Nederland is iets waar we aandacht aan moeten blijven besteden. “Wij Nederlanders dragen de erfenis van kolonialisme en exploitatie, dit verleden heeft ons gemaakt wie we nu zijn. Onze welvarende samenleving is tot stand gekomen doordat we profiteerden van de slavenhandel. Die historische rekenschap moeten we ons nu aantrekken.” Concludeert Raben.

Hoe we omgaan met het verleden heeft ook invloed op onze aanpak in de toekomst. Volgens Van Rinsum zouden we af moeten stappen van het problematische idee van ontwikkelingssamenwerking. “Wij wilden deel uitmaken van een beschavingsmissie om die anderen maar voortdurend te bekeren en te ontwikkelen, want die was nog niet zo ver. Ze helpen om ook zo ver te komen. Maar op die manier hebben we het koloniale systeem in stand gehouden.” Om voorbij dit paradigma van ontwikkeling te komen, moeten we volgens Van Rinsum focussen op het opzetten van samenwerkingen met landen in de Global South op een gelijkwaardige basis.

Kijk hier de avond ‘Wat we niet weten over ons slavernij verleden’ met onder anderen historicus dr. Remco Raben terug.